63

One of the signatories is Commodore

Isaac Hull, famous as the captain of

the USS Constitution, “Old Ironsides”,

during the War of 1812. Sharing in their

toasts on board the United States was

“His Excellency General Bolivar and

suite”, the Liberator himself proposing

a toast to his fellow liberator, Lafayette

(lot 223). On a less exalted – albeit

no less intriguing - level is a humble

commercial letter signed “Bakewell

Page & Bakewell” in which Lafayette is

presented with “a small token of the deep

sense we entertain, in common with our

fellow Citizens, of the obligations we owe

to your generous valour” (lot 239). This

small token took the form of two glass

vases made by Bakewell’s of Pittsburgh,

one engraved with a view of Lafayette’s

chateau, La Grange, the other with the

American Eagle. Bakewell’s was the

company which, that same year, took

out a patent for what was in effect the

world’s first method of mass-producing

glassware. And as a pendant to this

particular story, one might note that one

of the vases that accompanied this letter

recently was sold over over $250,000 at

auction.

In his letter inviting Lafayette to Michigan,

the explorer Lewis Cass highlights one

extraordinary quality that pervades

these papers, the sense that this was

one of those very few times in history

when history itself was revisited, a sense

almost of resurrection. Lafayette is hailed

as “the only Surviving Major General of

the revolutionary army among us”, and

told that he lives “in the midst of posterity

(…) you hear the judgment of history

upon your life and actions”. This archive

provides us not only with an extraordinary

snapshot of young America as it was in

1824-1825, of its own view of its glorious

past and burgeoning future, but in its

mingling of the humble and the grand,

the well-known and obscure, it could

be said to carry an emotional weight,

a fascination, possessed by few other

archives.

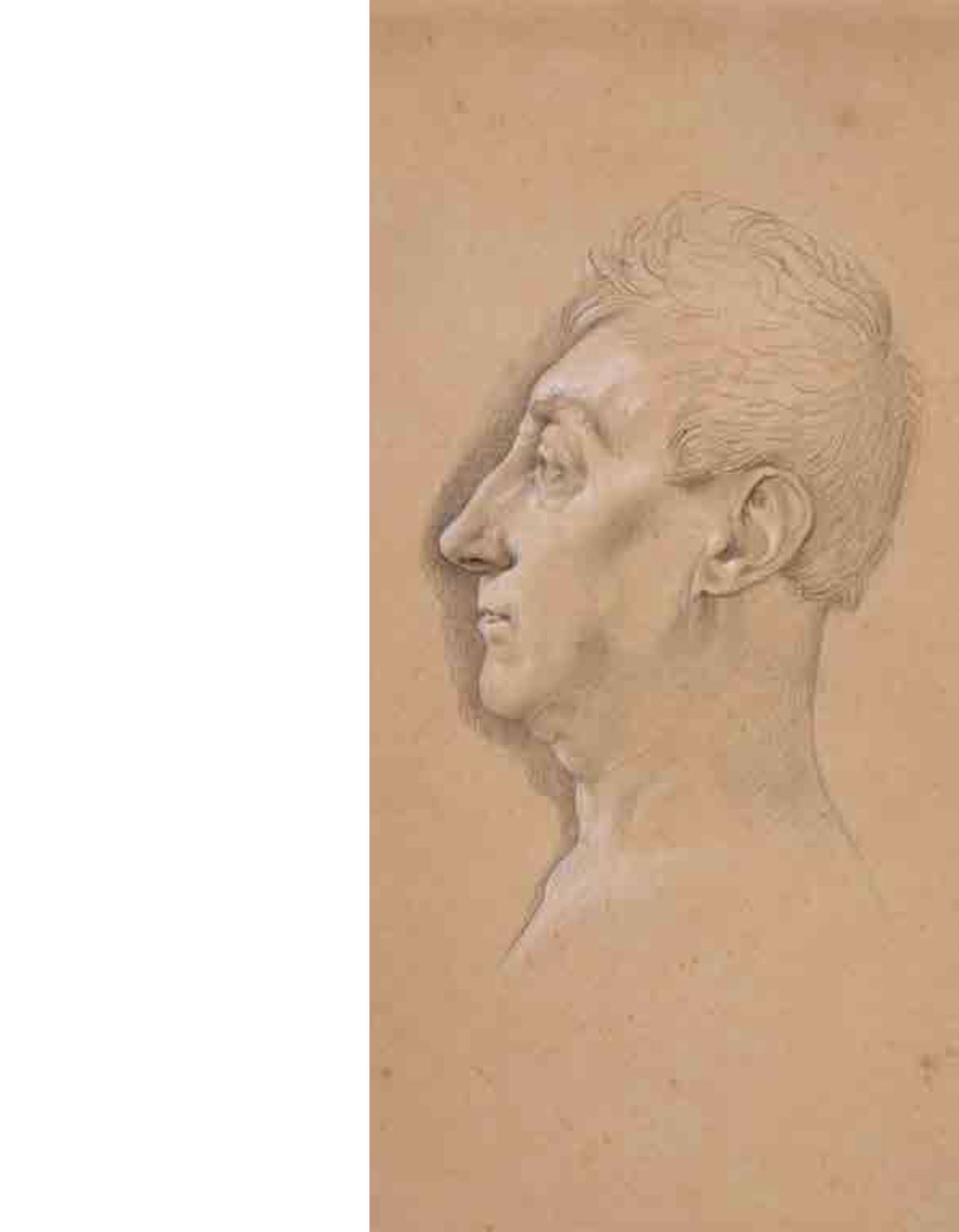

Portrait de Lafayette

par Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Bayonne, musée Bonnat.

©RMN-Grand Palais / René-Gabriel Ojéda