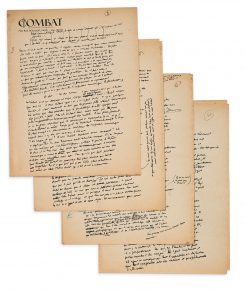

CAMUS Albert (1913-1960) — L'Homme révolté, fragment de manuscrit autographe [1950], 11 feuillets in-4 sur papier à entête de la revue Combat, numérotés de 2 à 12.

Description

Cet essai est avant tout un travail de recherche sur l'histoire et les formes de la révolte. Il est divisé en cinq chapitres, L'Homme révolté (introduction), La Révolte métaphysique, La Révolte historique, Révolte et art et La Pensée de Midi, chacun (hormis l'introduction) étant divisé en articles.

Les 11 feuillets du présent manuscrit correspondent aux articles Roman et révolte et Révolte et style, qui se suivent dans le IVe chapitre, Révolte et art. Ils forment un manuscrit qui constitue une importante variante contenant plusieurs passages non retenus dans la version publiée par Gallimard en 1951.

Ces feuillets proviennent du manuscrit Agnely, du nom de la secrétaire particulière d'Albert Camus, Suzanne Agnely. Cette variante a été en partie publiée dans les notes de l'édition de référence (Essais, Paris, Gallimard, 1965, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, pp. 1650 sqq.). Une part significative du texte, cependant, n'a pas été retranscrite et doit donc être considérée comme totalement inédite. Dans ces passages inédits, Camus défend et illustre sa conception du roman.

«C'est qu'il ne nous suffit pas de vivre, il nous faut des destinées sans attendre la mort. Oui, il est bien juste de dire que nous rêvons d'un monde meilleur que celui-ci. Mais meilleur ne veut pas dire ici bon au lieu de mauvais (et quel plaisir à lire cette désespérante Princesse de Clèves).

Meilleur veut dire conséquent et un. Cette fièvre qui nous emporte loin de ce monde éparpillé, c'est la fièvre de l'unité».

«Qu'est-ce que le roman en effet, sinon ce monde où l'action humaine reçoit sa forme, où les mots de la fin sont prononcés, les êtres livrés aux êtres et où toute vie prend le visage du destin. Qu'est-ce que le roman sinon la recréation de ce monde-ci selon le désir profond de l'homme».

─ L'on joint cinq brouillons de lettres autographes à divers correspondants non identifiés («Chère Mademoiselle», «Cher Monsieur», «Cher Camarade», etc..) en tout 9 pp. in-4 et in-8 autographes.

L'Homme révolté, fragment of an autograph manuscript [1950], 11 sheets in-4 on Combat magazine letterhead, numbered from 2 to 12. Precious and partly unpublished variant of L'homme révolté in which Albert Camus gives his definition of the novel and illustrates it with analyses by Flaubert, Proust and American novelists. Published after L'Étranger (1942) and La Peste (1947), L'Homme Révolté triggered a famous polemic on its release in October 1951 that ended up blurring the perception of this work. Sartre saw it above all as an anti-communist pamphlet and became definitively angry with Camus. This essay is above all a research work on the history and forms of the revolt. It is divided into five chapters, The Revolted Man (introduction), The Metaphysical Revolt, The Historical Revolt, Revolt and Art, and The Thought of Noon, each of which (apart from the introduction) is divided into articles. The 11 folios of this manuscript correspond to the articles Roman and Revolt and Revolt and Style, which follow each other in Chapter IV, Revolt and Art. They form a manuscript which constitutes an important variant containing several passages not retained in the version published by Gallimard in 1951. These leaves come from the Agnely manuscript, named after Albert Camus' private secretary, Suzanne Agnely. This variant was partly published in the notes of the reference edition (Essais, Paris, Gallimard, 1965, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, pp. 1650 ff.). A significant part of the text, however, has not been transcribed and must therefore be considered as completely unpublished. In these unpublished passages, Camus defends and illustrates his conception of the novel. "It is not enough for us to live, we need destinies without waiting for death. Yes, it is quite right to say that we dream of a better world than this one. But better doesn't mean good instead of bad (and what a pleasure it is to read this desperate Princess of Cleves). Better means consequent and one. This fever that carries us away from this scattered world is the fever of unity". "What is the novel indeed, if not this world where human action receives its form, where the words of the end are pronounced, the beings delivered to the beings and where all life takes the face of destiny. What is the novel if not the recreation of this world according to man's deepest desire". Five drafts of autograph letters to various unidentified correspondents ("Dear Miss", "Dear Sir", "Dear Comrade", etc.) are attached, in all 9 pp. in-4 and in-8 autographs.